Absolute vs. Relative Risk Calculator

How This Works

Enter your baseline risk (chance without treatment) and your new risk (chance with treatment). This calculator will show you the absolute difference, relative change, and Number Needed to Treat (NNT).

Your actual risk without treatment (e.g., 2% chance of heart attack)

Your risk with treatment (e.g., 1% chance of heart attack)

Results

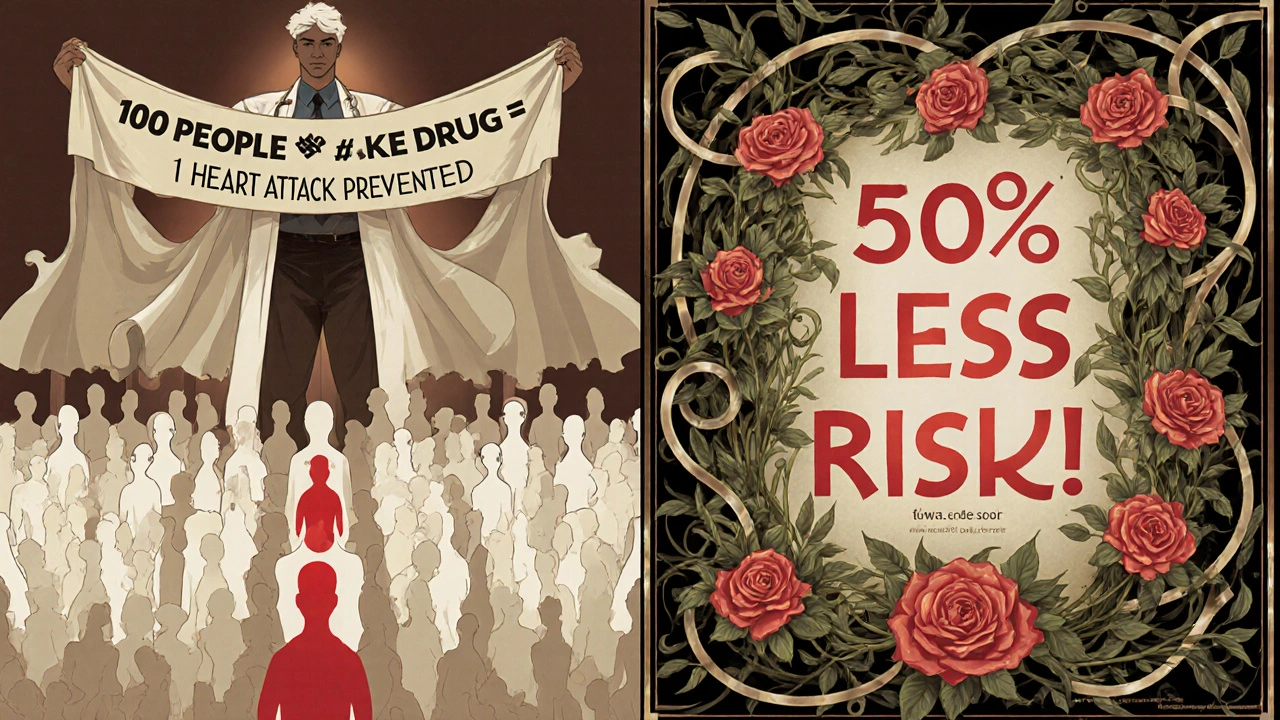

Imagine you’re told a new medication cuts your risk of a heart attack in half. That sounds impressive-until you find out your original risk was only 2%. Cutting it in half means going from 2% to 1%. That’s not a miracle drug. It’s a small benefit. But most ads don’t tell you that. They just say "50% reduction." And that’s where things get misleading.

What’s the Difference Between Absolute and Relative Risk?

Absolute risk is the real, actual chance something will happen to you. If 2 out of every 100 people in your group have a heart attack in a year, your absolute risk is 2%. Simple. Straightforward. It doesn’t change based on comparisons. Relative risk is a comparison. It tells you how much more or less likely something is in one group versus another. If a drug lowers heart attack risk from 2% to 1%, the relative risk reduction is 50%. That’s because 1% is half of 2%. But here’s the catch: the absolute risk only dropped by 1 percentage point. That’s the real impact. Think of it like this: Absolute risk tells you how big the puddle is. Relative risk tells you how much smaller it got after you dipped a towel in it. You need to know both to understand what actually happened.Why Do Drug Ads Use Relative Risk?

Pharmaceutical companies know that 50% sounds better than 1%. And it’s not just ads-it’s in clinical trial reports, doctor presentations, and even patient leaflets. A drug that reduces the chance of a rare side effect from 1 in 100,000 to 1 in 10,000,000 sounds amazing: a 99.9% relative risk reduction. But the absolute drop? Just 0.099%. That’s less than one extra person helped per 1,000 people taking the drug. This isn’t an accident. A 2021 study found that 78% of direct-to-consumer drug ads in the U.S. highlight relative risk reductions without mentioning absolute numbers. Why? Because bigger numbers sell. A 90% reduction sounds life-changing. A 0.1% reduction sounds negligible. But both can describe the same drug.How to Calculate Absolute and Relative Risk

Let’s break it down with numbers. Say 10 out of 100 people on a placebo (no drug) develop nausea. That’s a 10% absolute risk in the control group. Now, 15 out of 100 people on the new drug get nauseous. That’s 15% absolute risk in the treatment group. Absolute risk increase = 15% - 10% = 5 percentage points. So, for every 100 people taking the drug, 5 more get nauseous than if they hadn’t taken it. Relative risk = 15% ÷ 10% = 1.5. That means you’re 1.5 times more likely to get nauseous on the drug than off it. Relative risk increase = (1.5 - 1) × 100 = 50%. So, the risk went up by 50% relative to the placebo group. The same math works for benefits. If a drug reduces stroke risk from 4% to 3%: - Absolute risk reduction = 1 percentage point - Relative risk reduction = 25% (because 3% is 75% of 4%, so you’ve cut 25% of the original risk) The drug didn’t prevent 25% of strokes in everyone. It prevented one stroke per 100 people treated.

The Number Needed to Treat (NNT) and Harm (NNH)

This is where things get practical. NNT tells you how many people need to take a drug for one person to benefit. NNH tells you how many need to take it for one person to be harmed. If a drug reduces heart attacks from 2% to 1%, the absolute risk reduction is 1%. So the NNT is 1 ÷ 0.01 = 100. That means 100 people need to take the drug for one heart attack to be prevented. If a drug causes nausea in 15% of users versus 10% on placebo, the absolute risk increase is 5%. So the NNH is 1 ÷ 0.05 = 20. That means 20 people need to take the drug for one to get nauseous. NNT and NNH turn abstract percentages into real-world numbers. If you’re told you need to take a pill every day for a year to prevent one heart attack, but 1 in 20 people will get sick from it-you can decide if that trade-off is worth it.Real Examples That Mislead

In 2013, after the Fukushima nuclear disaster, headlines said cancer risk had "increased by 70%" in children. That sounds terrifying. But the actual absolute risk went from 0.75% to 1.25%. That’s a 0.5 percentage point increase. In a population of 10,000 kids, that’s 5 extra cases-not 70 extra cases. Another common example: statins. Many patients refuse them because they heard it "cuts heart attack risk in half." But if their baseline risk was 1%, cutting it in half means going to 0.5%. That’s one fewer heart attack per 200 people over 10 years. For someone with low risk, the benefit is tiny. For someone with high risk-say, 10%-it’s a much bigger deal. A 2022 Reddit thread had a primary care doctor say: "I had a patient refuse statins because they read online it cuts heart attack risk in half. They didn’t realize their risk was only 2% to begin with. They thought they’d go from 50% to 25%-not 2% to 1%."What Experts Say

Dr. Steve Woloshin and Dr. Lisa Schwartz from Dartmouth have spent years studying how medical numbers are presented. Their research shows that only 8% of patients can accurately interpret relative risk on its own. But when absolute risk is shown with visual aids-like a grid of 100 people, where 2 are colored red for risk-the number jumps to 62% understanding. They recommend always starting with absolute risk: "Your chance of having a stroke this year is 4%. This drug lowers it to 3%. That means for every 100 people like you, one stroke will be prevented. But 5 out of 100 will have a side effect like muscle pain." The European Medicines Agency now requires both absolute and relative risk in patient leaflets. The U.S. FDA has started pushing for the same, but enforcement is still weak. Many ads still hide the small absolute benefit behind big relative numbers.

How to Protect Yourself

You don’t need to be a statistician to understand your risks. Here’s what to ask:- "What’s my risk without the drug?"

- "What’s my risk with the drug?"

- "How many people need to take this for one person to benefit?"

- "How many people will have a side effect?"

- "Is this benefit or risk being shown as a percentage or as a real number?"

Why This Matters for Your Health

Misunderstanding risk leads to bad decisions. People skip life-saving drugs because they think the side effects are worse than the benefit. Others take drugs with tiny benefits and big side effects because they think the "50% reduction" means they’re protected. A 2019 study found that 60% of doctors couldn’t correctly convert a relative risk reduction to absolute terms. If your doctor doesn’t get it, how can you? The goal isn’t to scare you. It’s to give you real information. If a drug lowers your risk of a rare but serious side effect by 90%, but your original risk was 0.01%, that’s still just 0.001% lower. You’re not saving yourself-you’re saving one person in 10,000. On the flip side, if a drug reduces your risk of death from 10% to 5%, that’s a 50% relative reduction-and a 5 percentage point absolute drop. That’s a major win. You need the numbers to know which is which.What’s Changing

More medical schools now teach risk interpretation. Harvard added a required course in 2022 after finding 68% of graduating students couldn’t interpret basic stats. The Cochrane Collaboration has created standard templates for reporting risk that 37 journals now use. By 2025, 90% of clinical trial registries will require both absolute and relative risk data to be submitted. That’s up from 65% in 2020. It’s slow, but it’s moving. The problem isn’t the math. It’s the presentation. When you see "reduces risk by X%," always ask: "Reduced from what?" That one question gives you control over your health decisions.Don’t let percentages trick you. Numbers don’t lie-but how they’re shown can.

What’s the difference between absolute risk and relative risk?

Absolute risk is your actual chance of something happening-for example, a 2% chance of having a heart attack this year. Relative risk compares your risk with or without a drug. If a drug lowers your heart attack risk from 2% to 1%, the relative risk reduction is 50% because you’ve cut the risk in half. But the absolute drop is just 1 percentage point. Absolute risk tells you the real impact; relative risk tells you the size of the change compared to something else.

Why do drug ads use relative risk instead of absolute risk?

Relative risk numbers are bigger and sound more impressive. Saying a drug "cuts heart attack risk by 50%" sounds better than saying it "lowers your risk from 2% to 1%." Pharmaceutical companies know this and use relative risk in ads because it drives prescriptions. But it hides the truth: the actual benefit for most people is often very small.

What is Number Needed to Treat (NNT)?

NNT tells you how many people need to take a drug for one person to benefit. If a drug reduces heart attack risk from 2% to 1%, the absolute benefit is 1%. So NNT = 1 ÷ 0.01 = 100. That means 100 people must take the drug for one heart attack to be prevented. It helps you weigh the benefit against possible side effects.

Can relative risk be misleading?

Yes, very. A drug might show a 90% relative risk reduction for a side effect, but if the original risk was 0.001%, the absolute drop is just 0.0009%. That’s almost no real-world benefit. Relative risk alone ignores the starting point. Always ask: "Reduced from what?"

How can I better understand my medication risks?

Ask your doctor for the absolute risk with and without the drug. Request the NNT (Number Needed to Treat) and NNH (Number Needed to Harm). Look for visual tools like pictograms showing 100 people with some shaded to represent risk. If you see "reduces risk by X%," always ask for the baseline number. Don’t rely on headlines or ads.

17 Comments

They don't tell you this because if they did, nobody would take the damn pills. I had my doctor push me on statins for 3 years before I finally asked, 'So how many people like me have to take this for one heart attack to be avoided?' He looked at me like I'd asked him to recite the Gettysburg Address in Klingon. Turns out, 100. One hundred people. For one guy to not get a heart attack. Meanwhile, 5 of us get muscle pain, liver issues, or just feel like zombies. I'm not taking a daily pill for a 1% shot at avoiding something that might never happen. Not when the side effects feel like a slow drip of my soul.

This is one of those things that makes me love medical literacy. People think '50% reduction' means they're basically invincible now. But if your baseline risk was 0.5%, you're now at 0.25% - which is still basically zero. It’s like saying you reduced your chance of being struck by lightning by half. Cool, but you were never going to get struck anyway. The real value is in the NNT. If 100 people have to take it for one benefit? That’s not a miracle. That’s a gamble. And I don’t gamble with my body.

Thank you for this. As someone who teaches health communication, I see this every day. Patients walk in convinced they’re 'saving their life' with a drug that reduces their risk from 2% to 1%. They’re not saving their life - they’re avoiding a single event that may never occur. The language of medicine is weaponized. We need to teach absolute risk from middle school. Not just in bio class - in civics. Because your health isn’t a marketing campaign. It’s your body. And you deserve to know the truth, not the spin.

I just read this and immediately thought of my mom… she took that 'miracle' cholesterol drug for 5 years, had terrible muscle pain, and still had a minor stroke… because she thought '50% reduction' meant she was safe. She didn’t know her baseline was 1.8%. That’s not a miracle. That’s a trap. Please, if you’re on meds, ask for the numbers. Not the hype. Ask for the real numbers. Please.

My cardiologist showed me a pictogram once - 100 little people, 2 red, 1 red turned blue after the drug. I finally got it. That’s the way to teach this. Not percentages. Not 'reductions.' Pictures. Real visuals. People get it when they see it. The FDA should mandate pictograms on every drug ad. Like tobacco warnings. Because right now, we’re letting pharma sell fear and false hope.

As someone from India where access to healthcare is uneven, this hits hard. We’re told 'this drug saves lives' - but rarely told who it actually saves. In rural clinics, they hand out statins like candy. No baseline risk checked. No NNT explained. People take them because the doctor said so. And when side effects hit? No one’s there to help. We need this kind of education at the grassroots level - not just in glossy medical journals. Real people need real numbers.

Oh wow, so the entire pharmaceutical industry is just… lying? Shocking. Next you’ll tell me water is wet and gravity exists. I mean, who knew? The same people who told me 'low-fat' foods were healthy, and now I’m eating butter like a caveman? Yeah, I’m not surprised. But hey, at least they’re consistent - lying is their core business model. Pass the placebo.

Love this. I’m a nurse and I see patients cry because they think they're 'not doing enough' if they don't take the drug that 'cuts risk by 50%.' But when I show them the actual numbers - 1 in 100 benefit, 1 in 20 get side effects - they breathe a sigh of relief. They feel empowered. Not guilty. This isn’t just math. It’s emotional labor. We need more of this kind of clarity.

My aunt took that new Alzheimer’s drug last year. 'Reduces progression by 27%!' the ad said. I dug into the study. Baseline risk of decline in 12 months? 12%. Post-drug? 8.76%. So… 3.24% absolute reduction. NNT of 31. And she got diarrhea every day. She stopped after 3 months. No one told her. She just felt guilty for 'not sticking with it.' We owe people better than this.

so like… if my risk is 2% and the drug makes it 1%… then i’m still at 1%? so why am i taking it? i mean, i could just eat better and be fine? why is everyone so scared of the 1%? it’s not like i’m gonna die tomorrow. this whole thing is wild.

Let me tell you what they’re not telling you. This isn’t about math. It’s about control. The pharmaceutical industry, the FDA, the AMA - they all work together. They want you dependent. They want you believing you need a pill for every little thing. The real risk isn’t heart attacks - it’s losing your autonomy. They’ve been conditioning us for decades. 'Take this for your cholesterol.' 'Take this for your sleep.' 'Take this for your mood.' But they never tell you the truth: your body can heal itself if you stop listening to the ads. The 50% reduction? It’s a distraction. A smoke screen. They’re not selling medicine. They’re selling obedience.

Did you know that the FDA has been quietly pressured by Big Pharma to suppress absolute risk data since the 90s? I’ve got documents. Emails. Internal memos from Merck, Pfizer, Novartis - all saying 'emphasize relative risk to avoid patient confusion.' But the real reason? Confused patients buy more drugs. And guess what? They’ve been testing this on children’s health pamphlets too. The '50% reduction' on ADHD meds? Baseline risk? 0.3%. So now your kid is on Adderall for a 0.15% absolute gain. And the side effects? Insomnia, weight loss, anxiety. But hey - it’s 'effective.' The system is rigged. And they’re not just lying. They’re grooming a generation to trust pills over intuition.

OMG this is so important!! 💯 I literally just had my doctor say 'this reduces your risk by 40%' and I was like... 40% of WHAT?? 😭 I almost cried because I thought I was saving my life and now I realize I’m just a number in a spreadsheet. I need a pictogram!! 🖼️ I’m going to print this out and tape it to my fridge. #MedicalTransparency #AskForTheNumbers

They’re hiding the truth because they know if people understood this, they’d stop taking everything. Statins? Placebos. Antidepressants? Placebos. Vaccines? Placebos. It’s all a money scheme. The 'benefits' are fabricated. The side effects are covered up. The studies are paid for by the same companies selling the pills. You think this is about health? It’s about profit. And you? You’re the product. Wake up.

Absolute risk is the actual chance. Relative risk is the comparison. NNT is how many need to take it for one benefit. NNH is how many get harmed. Ask for all four. Don’t accept vague percentages. This is basic. Everyone should know this.

This is the essence of human wisdom - understanding scale. A drop of water in an ocean is still a drop. But if you’re the drop, you feel the change. We must learn to see both the ocean and the drop. Medicine is not magic. It’s math with consequences. And we, as people, deserve to see the whole picture - not just the glittering headline. The truth is not always loud. But it is always there. Waiting for us to ask the right question.

lol i just took a pill because it said 'cuts heart attack risk in half' now i realize i was already at 1% so i just went to 0.5%?? like… i’m still gonna die of something else so why care??