When a child can’t swallow a pill, hates the taste of medicine, or needs a dose that doesn’t come in a store-bought bottle, compounded medications can seem like a lifesaver. But behind that custom liquid or flavored gel is a hidden risk: compounded medications for children aren’t tested or approved by the FDA. That means no one guarantees they’re safe, accurate, or even made in a clean environment. For parents, this isn’t just about convenience-it’s about avoiding a mistake that could land their child in the hospital.

Why Compounded Medications Are Used for Kids

Compounded medications are made by pharmacists to fit a child’s exact needs. Common reasons include:- Children who can’t swallow pills need liquids, chewables, or even topical gels

- Flavoring bitter drugs so kids will actually take them

- Removing allergens like dyes, alcohol, or gluten

- Creating sugar-free versions for diabetic children

- Preparing tiny doses of powerful drugs like morphine or fentanyl for newborns

These aren’t just nice-to-haves-they’re often necessary. A 5-pound premature infant can’t take the same dose as an adult. A child with a severe food allergy might react to a common preservative in commercial meds. But here’s the catch: if an FDA-approved version exists, it should be used instead. The FDA warns that unnecessary compounding exposes kids to avoidable dangers.

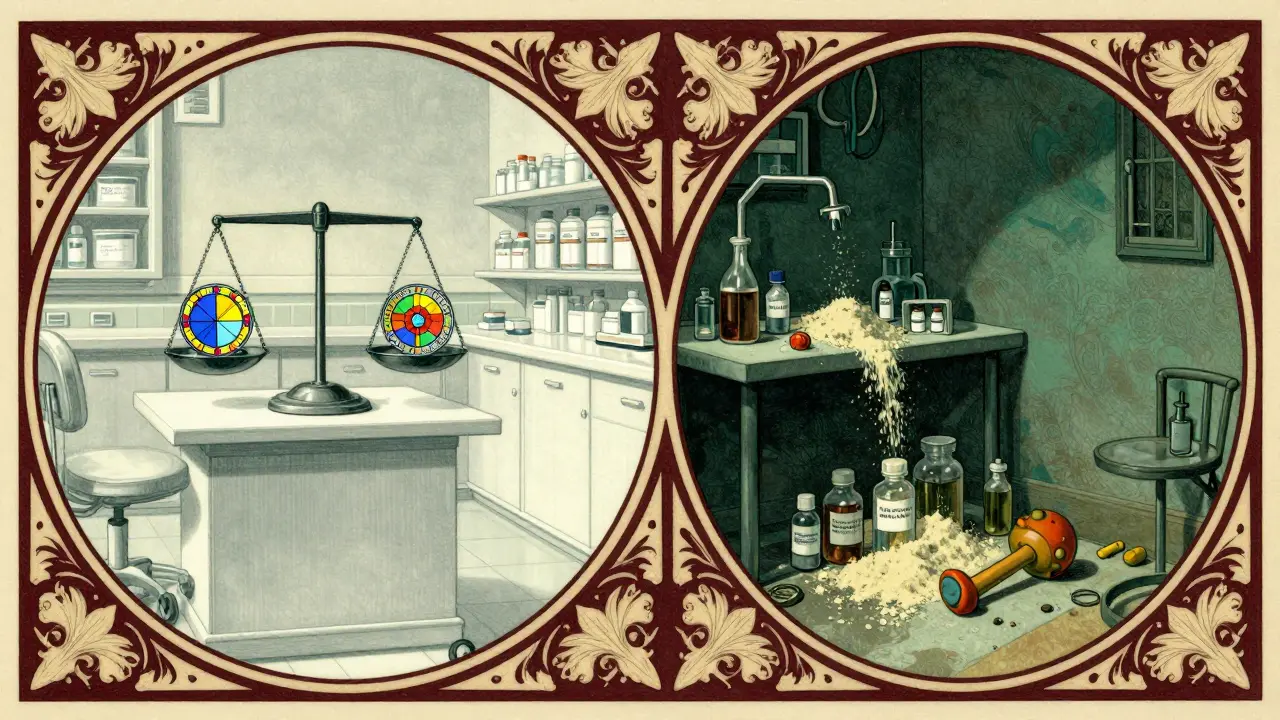

The Hidden Dangers of Compounded Drugs

Compounded medications aren’t subject to the same checks as regular drugs. That means:- The strength might be wrong-too weak or too strong

- The ingredients might be contaminated

- The flavoring might mask the taste but hide the real problem

In 2006, two-year-old Emily Jerry died after receiving a compounded chemotherapy dose that was 10 times too strong. The error happened because the pharmacy used volume-based measuring instead of precise weight-based methods. Her death led to the creation of the Emily Jerry Foundation, which now pushes for mandatory use of gravimetric analysis-technology that weighs ingredients instead of guessing by volume.

Fast forward to 2024: over 900 adverse events linked to compounded semaglutide and tirzepatide were reported to the FDA, including 17 deaths. Pediatric patients were disproportionately affected, with vomiting, dehydration, and hypothyroidism linked to inaccurate doses. One parent on Reddit shared that their 8-year-old ended up in the ER after a compounded levothyroxine dose was 40% weaker than prescribed. That’s not a rare glitch-it’s a pattern.

Where Things Go Wrong

Most errors happen because of simple mistakes:- Wrong concentration: A pharmacist writes “10 mg/mL” but the parent reads it as “10 mg per teaspoon” without knowing how many mL are in a teaspoon

- Improper storage: Some compounded meds need refrigeration but are left on the counter

- Outdated formulas: A pharmacy uses old recipes even after new guidelines are published

- Lack of training: Not all pharmacists are trained in pediatric dosing-some only do 2 hours of training, when 40+ hours are recommended

A 2022 study from SafeMedicationUse.ca found that 68% of pediatric compounding errors came from miscommunication about concentration units. One parent thought they were giving 5 mL of a 1 mg/mL solution. The pharmacist meant 5 mL of a 1 mg/5 mL solution. The child got 5 times the intended dose.

How to Spot a Safe Compounding Pharmacy

Not all compounding pharmacies are the same. Here’s how to find one that prioritizes safety:- Check for PCAB or NABP accreditation

- Ask if they use gravimetric analysis (weighing ingredients, not measuring by volume)

- Verify they follow USP Chapter <797> standards for sterile compounding

- Ask if they do independent double-checks on every pediatric dose

Only about 1,400 of the 7,200 compounding pharmacies in the U.S. are accredited by PCAB. That means over 80% aren’t held to the highest safety standards. If your pharmacy doesn’t mention accreditation, ask why. A reputable pharmacy will be proud to show you their credentials.

What Parents Must Do Before Giving the Medication

You’re the last line of defense. Don’t assume the pharmacist got it right. Do this before giving any compounded medicine to your child:- Ask for the exact concentration-not just the total dose. Write it down: “10 mg per 5 mL,” not “10 mg.”

- Double-check with your doctor. Call the prescriber and confirm the dose, concentration, and frequency.

- Use the right measuring tool. Never use a kitchen spoon. Use the syringe or cup the pharmacy provides-or buy a calibrated oral syringe from a drugstore.

- Check the label. Does it say “For Pediatric Use Only”? Is there an expiration date? Is it refrigerated if needed?

- Watch for changes. If the color, smell, or texture looks different from the last time, don’t give it. Call the pharmacy.

One parent in a 2024 Harvard Health report gave their child a compounded version of a common antibiotic. The bottle looked fine. But the child started vomiting within an hour. The pharmacy had accidentally used a different salt form of the drug-something that’s not always obvious on the label.

When to Avoid Compounded Medications Altogether

Sometimes, the risk isn’t worth it. Walk away if:- An FDA-approved version exists-even if it’s not flavored or comes in a pill

- The pharmacy can’t prove accreditation or doesn’t use gravimetric analysis

- The dose is for a neonate or infant under 10 pounds-these tiny patients are at highest risk

- The medication is a high-risk drug like fentanyl, morphine, or thyroid hormone

For newborns in the NICU, the safest option is always a premixed, commercially prepared IV bag. Manual compounding-even by the best pharmacist-carries too much risk. The same goes for GLP-1 drugs like semaglutide. The FDA has documented dozens of pediatric hospitalizations from compounded versions. These drugs were never meant to be compounded for children.

What’s Being Done to Fix This

Change is slow, but it’s coming. The Emily Jerry Foundation has pushed for “Emily’s Law,” which now requires gravimetric analysis for pediatric sterile compounding in 28 states. The FDA has issued new draft guidelines in 2024 to crack down on pharmacies that exploit drug shortages to mass-produce compounded drugs. The ISMP is developing new pediatric safety metrics to be released in late 2025.But the biggest barrier? Cost. Gravimetric equipment runs $25,000 to $50,000 per station. Most small pharmacies can’t afford it. That’s why rural areas and low-income clinics still rely on outdated, error-prone methods. Until funding and training improve, the burden falls on parents to be vigilant.

Final Word: Trust, But Verify

Compounded medications can help children when nothing else works. But they’re not magic. They’re a last resort-and they demand extreme caution. The same pharmacy that makes a safe, tasty liquid for your child’s antibiotic might also make a dangerous, untested version of a powerful drug. You can’t assume safety. You have to demand proof.Ask questions. Write things down. Double-check. If a pharmacist seems annoyed by your questions, walk out. Your child’s life isn’t worth the convenience of a quick fix.

Are compounded medications FDA-approved?

No. Compounded medications are not FDA-approved. The FDA does not test them for safety, effectiveness, or quality before they’re given to patients. This is why it’s critical to use only accredited pharmacies and verify every detail with your doctor and pharmacist.

How do I know if my child’s compounded medicine is safe?

Check if the pharmacy is accredited by PCAB or NABP. Ask if they use gravimetric analysis (weighing ingredients) instead of volume-based measuring. Confirm the concentration (e.g., 5 mg/mL), not just the total dose. Verify storage instructions and expiration dates. If anything seems off, call the pharmacy and your doctor before giving it.

Can I use a kitchen spoon to measure my child’s compounded medicine?

Never. Kitchen spoons vary wildly in size. A teaspoon can hold anywhere from 3 to 7 mL. Always use the syringe or dosing cup provided by the pharmacy. If you lose it, buy a calibrated oral syringe from a drugstore. Precision matters-even a 1 mL error can be dangerous in a small child.

What should I do if my child has a bad reaction to a compounded drug?

Stop giving the medication immediately. Call your doctor or go to the ER. Report the reaction to the FDA’s MedWatch program and to the pharmacy. Keep the bottle and packaging. These reports help regulators track dangerous patterns and protect other children.

Is it safer to get a compounded medication from a hospital pharmacy or a regular pharmacy?

Hospital pharmacies are generally safer because they follow strict USP <797> standards, use gravimetric analysis, and have independent double-checks for every pediatric dose. Community pharmacies vary widely in quality. If possible, ask your doctor to prescribe through a hospital or accredited compounding pharmacy.

Why do some doctors prescribe compounded medications instead of FDA-approved ones?

Sometimes, there’s no FDA-approved option that fits the child’s needs-like a flavor-free, sugar-free, preservative-free liquid. Other times, doctors may not realize an approved version exists, or they’re pressured by parents who want a better-tasting version. Always ask: “Is there an FDA-approved alternative?” If the answer is yes, insist on it.

11 Comments

Oh, of course-the FDA doesn’t regulate compounding? How shocking. Next you’ll tell me that the moon landing was faked and my kale smoothie is secretly a government bioweapon. At this point, every pill I swallow should come with a notarized affidavit from a pharmacist in a hazmat suit. Truly, we live in the golden age of medical paranoia.

Wait-so you’re telling me that a pharmacy, with NO oversight, can just mix up a vial of morphine for a 3-pound preemie and no one’s checking? And you want me to trust them because they have a sticker on the wall that says ‘PCAB Accredited’? That’s like trusting a guy who says he’s a doctor because he watched House for 12 hours! This isn’t medicine-it’s Russian roulette with a syringe.

bro i gave my kid a compounded version of amoxicillin and he was fine. i used the syringe, checked the label, called the doc. if you’re scared, don’t use it. but don’t scare everyone into thinking every pharmacist is a mad scientist. some of us just want our kids to take their meds without screaming like a banshee.

Thank you for this meticulously researched and sobering overview. The distinction between necessity and convenience in compounding is ethically and clinically paramount. I have worked in pediatric oncology for over seventeen years, and I can confirm that when compounded medications are used under strict, accredited protocols-with gravimetric analysis, double verification, and clear communication-they can be life-saving. The danger lies not in the practice itself, but in its unregulated proliferation. We must advocate for systemic reform, not fear.

I remember the first time my daughter refused her antibiotics because they tasted like burnt plastic. We tried everything-chocolate syrup, popsicle molds, even hiding it in peanut butter (don’t do that, by the way, it messes with absorption). Then we found a compounding pharmacy that made it taste like bubblegum. She took it like candy. But I didn’t just take their word for it. I called the pharmacy. I asked for the batch number. I verified the concentration with my pediatrician. I used the syringe. I kept the bottle. And yes-I cried when I saw the expiration date. Because I knew: this isn’t just medicine. It’s a promise. And promises can break.

THIS IS WHY AMERICA IS FALLING APART. We let some guy in Ohio with a $500 mixer and a pharmacy degree decide how much morphine a baby gets? And you want to trust ‘accreditation’? HA! The FDA is a joke. We need a national registry. We need armed inspectors. We need to burn down every unaccredited pharmacy and replace them with military-grade labs. This isn’t healthcare-it’s a horror movie written by Big Pharma and watched by dumb parents.

Let’s not forget the 2012 New England Compounding Center meningitis outbreak that killed 76 people. That was sterile compounding. Now imagine non-sterile, non-validated, non-audited pediatric compounding. The 2024 FDA data on semaglutide is not an anomaly-it’s the tip of an iceberg. The USP Chapter <797> standards exist for a reason. If your pharmacy doesn’t cite them explicitly, they’re not following them. And if they’re not following them, they’re gambling with your child’s life. Gravimetric analysis isn’t optional. It’s non-negotiable. Period.

There is a profound irony in our medical ecosystem: we demand perfection from pharmaceutical manufacturers, yet we outsource the most delicate dosing tasks-where precision is literally a matter of life or death-to underfunded, undertrained, and under-audited entities. We have created a system where the most vulnerable among us are subjected to the whims of economic pragmatism disguised as innovation. The solution is not parental vigilance alone. It is structural. It is fiscal. It is moral. We must fund, regulate, and elevate compounding to the standard of surgical care-not treat it like a side hustle for pharmacists with too much time and too little oversight.

Oh, so now we’re blaming pharmacists? What about the doctors who prescribe these things without checking if an FDA version exists? Or the parents who demand ‘flavored’ versions because they’re too lazy to fight with their kid? This isn’t a pharmacy problem-it’s a society problem. Everyone wants convenience without responsibility. You want safety? Stop asking for unicorn potions. Use the pill. Suck it up. Your kid will live. And if they don’t? Well, that’s what autopsies are for.

Interesting. In India, compounded pediatric formulations are common due to cost and availability. But we have strict guidelines from the Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission. Pharmacies are required to maintain batch records and undergo periodic inspections. I wonder if the U.S. could adopt a hybrid model-market-driven innovation with centralized oversight. The technology exists. The will? That’s the question.

my kid’s compounding pharmacy gave me a label that said ‘5mg/5mL’ but i thought it was 5mg/mL. i gave him the wrong dose. he was fine. i felt like an idiot. now i always use the syringe and call the doc. just… be careful. it’s not that hard.