Opioid-Antiemetic Interaction Checker

Check for Dangerous Interactions

Select medications to see potential risks based on clinical evidence from the article.

When patients start opioids for pain, nausea and vomiting often come along for the ride. It’s not rare-it happens in 20 to 33% of people, according to clinical studies. For many, this isn’t just uncomfortable; it’s a dealbreaker. One study found that patients would rather endure more pain than deal with nausea from opioids. That’s how powerful this side effect is. And yet, too many providers still default to prescribing antiemetics upfront, without thinking through the risks or the real need.

Why Opioids Make You Nauseous

Opioids don’t just block pain-they mess with multiple systems in your body. The nausea doesn’t come from one single cause. It’s a mix of three key mechanisms:- Slowed gut movement: Opioids activate mu-receptors in the intestines, which slows digestion. That buildup triggers signals to the brain that feel like nausea.

- Chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ) stimulation: This area in the brainstem has dopamine receptors. Opioids activate them, tricking the brain into thinking there’s poison in the system.

- Vestibular sensitivity: Some people feel dizzy or nauseous when they move, especially after lying down. Opioids heighten sensitivity in the inner ear, making motion feel overwhelming.

This complexity is why a one-size-fits-all antiemetic doesn’t work. What helps one person might do nothing for another.

The Problem with Routine Prophylaxis

For years, doctors routinely gave metoclopramide or ondansetron before starting opioids-just in case. But recent evidence says that’s not the right move.A 2022 Cochrane review looked at three studies where patients got metoclopramide before IV opioids. Result? No reduction in nausea or vomiting. No benefit. Not even a hint. And the studies weren’t small-they included over 300 patients total. That’s not a fluke.

Why does this happen? Because nausea from opioids often fades on its own. Most patients develop tolerance within 3 to 7 days. Giving an antiemetic on day one might be unnecessary-and risky.

Take ondansetron, for example. It’s effective for treating nausea once it starts. But it also carries a black box warning from the FDA. It can prolong the QT interval, leading to dangerous heart rhythms. Droperidol, another common choice, has the same warning. You’re trading a short-term discomfort for a potential cardiac risk.

When Antiemetics Actually Help

There are times when antiemetics are necessary. The key is matching the drug to the cause.- For CTZ-driven nausea (dopamine effect): Try low-dose haloperidol or prochlorperazine. These block dopamine receptors without the QT risk of ondansetron.

- For gut-related nausea: Metoclopramide can help-but only if used short-term. It’s a prokinetic, meaning it speeds up the gut. But it can cause muscle spasms or restlessness if used too long.

- For dizziness or motion-triggered nausea: Scopolamine patches or meclizine work better. They target the vestibular system, not the brainstem.

- For severe or persistent cases: Palonosetron is stronger than ondansetron. One study showed only 42% of patients on palonosetron had nausea vs. 62% on ondansetron.

Don’t guess. Ask: Is the nausea worse when standing? Then it’s vestibular. Is it constant, even at rest? Then it’s likely from the CTZ or gut. That changes your drug choice.

Drug Interactions You Can’t Afford to Miss

Opioids don’t play nice with other meds. Mixing them with antiemetics is risky-but mixing them with antidepressants or migraine drugs? That’s dangerous.The FDA has issued clear warnings: combining opioids with SSRIs, SNRIs, triptans, or MAOIs can cause serotonin syndrome. Symptoms include high fever, rapid heart rate, confusion, muscle rigidity, and seizures. It’s rare, but it kills.

And it’s not just serotonin. Antiemetics like droperidol or metoclopramide can add to sedation when combined with opioids. That means slower breathing, lower blood pressure, and a higher risk of overdose.

Always check for interactions. A patient on fluoxetine for depression who starts oxycodone? That’s a red flag. A patient on sumatriptan for migraines getting morphine? That’s a warning sign. These aren’t edge cases-they’re common.

Best Practices: What Actually Works

There are four proven strategies for managing opioid-induced nausea and vomiting (OINV). None of them involve automatically reaching for an antiemetic.- Start low, go slow. A 1 mg oral morphine dose twice daily is often enough for mild pain. Pushing higher doses too fast guarantees side effects. Let the body adjust.

- Rotate opioids. Not all opioids cause nausea the same way. Oxymorphone has a 60 times higher risk per dose than oxycodone. Tapentadol has much lower nausea risk. Switching can eliminate nausea without losing pain control.

- Adjust the dose. If nausea is bad, lower the opioid by 25-30%. Often, pain stays controlled. You don’t need to max out the dose to get relief.

- Use antiemetics only when needed. Wait until nausea appears. Then pick the right drug for the suspected cause. Don’t give it preemptively.

The CDC’s 2022 guideline says it plainly: “Advise patients about common effects of opioids, such as nausea and vomiting.” That’s not optional. It’s standard care. Patients need to know this might happen-and that it usually gets better.

What About Chronic Pain?

Most opioids are meant for short-term use-after surgery, injury, or cancer pain. But too many patients stay on them for years. That’s where the real danger lies.Long-term opioid use increases tolerance to pain relief but not to nausea. That means nausea sticks around, even if the pain improves. At the same time, constipation gets worse, sedation builds, and risk of overdose climbs.

For chronic pain, opioids should be a last resort. Non-opioid options-physical therapy, nerve blocks, gabapentin, even cognitive behavioral therapy-often work better and safer. If opioids are still needed, the goal isn’t to manage nausea forever. It’s to get off them.

Final Takeaway: Less Is More

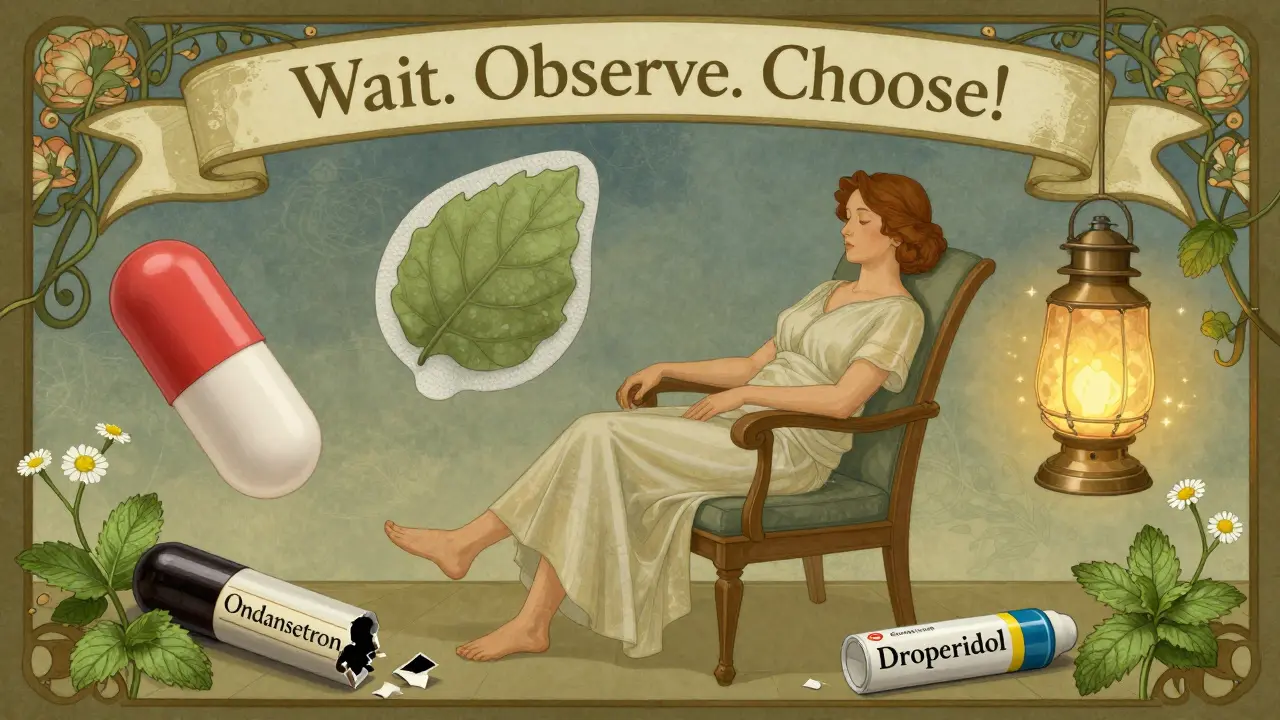

The biggest mistake? Treating nausea like a bug to be eradicated. It’s a signal. It’s your body telling you the opioid dose is too high, the wrong drug, or the patient isn’t ready.Don’t rush to an antiemetic. Don’t assume it’s needed. Don’t ignore drug interactions.

Start low. Watch for symptoms. Tailor treatment. Educate the patient. And remember: most nausea fades in a week. You don’t need to fix it with a pill. Sometimes, you just need to wait.

13 Comments

Let me cut through the noise here - prescribing antiemetics upfront is lazy medicine. I've seen patients crash on QT-prolonging drugs because some doc thought it was easier to throw on ondansetron than wait three days. The body adapts. Nausea isn't a bug, it's a feature of opioid adaptation. Stop treating symptoms like emergencies. Start treating them like signals.

It's fascinating how we've institutionalized fear of discomfort in medicine. We're so terrified of patients feeling even mildly ill that we've created a pharmacological arms race against nausea - a transient, self-limiting side effect - while ignoring the deeper question: why are we giving opioids at all? The real tragedy isn't the vomiting, it's that we've normalized chronic opioid use as a default for chronic pain, then medicate the side effects into a new kind of dependency. We're not treating patients; we're managing systems.

Man, this is the kind of post that makes me wanna high-five someone in a hospital hallway. Finally someone gets it - nausea isn't a villain, it's a messenger. I used to hand out ondansetron like candy until I realized half my patients were just getting used to the opioid. Now I say, 'Hold off for 72 hours, let your body chill.' And guess what? Most of them don't even come back. The real win? Fewer ER visits, fewer heart risks, and patients who actually feel heard instead of dosed.

Cochrane review? 300 patients? That's underpowered. You're cherry-picking data. Metoclopramide's bioavailability varies by renal function, and ondansetron's QT risk is negligible in low doses. You're oversimplifying a complex pharmacokinetic problem. Also, palonosetron data is from cancer patients - not post-op or chronic pain. Your 'best practices' ignore real-world heterogeneity. This reads like a blog post masquerading as clinical guidance.

I’ve worked in oncology for 18 years. I’ve seen patients cry because they couldn’t keep water down after their first morphine dose. You’re right - many cases resolve. But waiting doesn’t mean ignoring suffering. Sometimes, a single dose of prochlorperazine is the difference between a patient staying compliant and quitting opioids entirely. It’s not about blanket prophylaxis - it’s about compassionate, individualized timing.

Love this. In India we don't even think about antiemetics unless nausea lasts more than 3 days. We tell patients: 'Wait, drink ginger tea, move slowly.' Most get better. Doctors here are scared of opioids - but not because of nausea. Because of addiction. We need more posts like this.

Thank you for writing this. I’m a nurse in a rural clinic. We don’t have specialists on call. When a patient starts opioids, I have to decide fast. This gives me clarity. I’ve started waiting 48 hours before offering anything. One woman said, 'I thought I’d have to stop the pain meds, but I didn’t even need the pill.' That’s the kind of win we need more of.

There's a critical epistemological flaw in the assumption that 'nausea resolves in 3–7 days' - this presumes a homogeneous pharmacodynamic response across opioid receptor subtypes, neuromodulatory pathways, and GI motility profiles. The Cochrane review cited fails to account for polymorphisms in CYP2D6 and ABCB1 transporters, which significantly alter metabolite accumulation and central dopamine receptor occupancy. Without stratifying by genotype, the 'no benefit' conclusion is statistically invalid. Furthermore, the QT risk of ondansetron is dose-dependent - 4 mg IV has a 0.03% incidence of torsades, while 8 mg carries 0.2%. The blanket avoidance of antiemetics ignores pharmacogenomic nuance.

How is it possible that someone with a medical degree could write something so… amateurish? You cite a Cochrane review and then ignore the fact that nausea in elderly patients with renal impairment requires prophylaxis. You dismiss droperidol as if it’s a novelty drug - it’s been used safely in 10 million ED visits. Your 'start low' advice is dangerous for cancer patients with breakthrough pain. This isn't clinical guidance - it's a TikTok trend dressed in medical jargon.

They told me I’d get used to it… but no one told me how heavy the silence would feel when you’re too nauseated to speak, too dizzy to cry, and too afraid to ask for help. I waited seven days. I almost didn’t make it. Sometimes waiting isn’t strength - it’s abandonment.

Just wanted to say I appreciate how you didn’t just say 'don't give drugs' - you gave real alternatives. I’m a med student and this is the kind of thinking I want to bring into my practice. Not just 'what drug to avoid' but 'what to do instead.' Thank you.

Oh please. You're telling me we shouldn't use antiemetics because 'most nausea fades'? What about the 20% who don't? The ones who get dehydrated, lose weight, miss work, or end up in the ER? You're romanticizing suffering. This isn't philosophy - it's negligence wrapped in a buzzword. If you're going to tell people to wait, at least have the guts to say 'and here's what to do if they don't get better.' You didn't.

It's ironic. You spend 2000 words warning against overmedicating nausea… and then you prescribe palonosetron like it's a magic bullet. You still want to fix it with a pill. You just changed the pill. You didn't change the mindset. You're still treating the symptom - not the cause. The cause is opioid overuse. And you still think it's okay to use them at all.