High Uric Acid – What It Means and How to Lower It

When dealing with high uric acid, an excess of uric acid in the blood that can lead to joint pain, kidney problems, and other health issues. Also known as hyperuricemia, it often signals an imbalance in metabolism, diet, or kidney function. high uric acid is not just a lab number; it’s a signal that your body is struggling to clear purine by‑products. Understanding this signal helps you spot the first signs before they turn into full‑blown gout attacks or kidney stones.

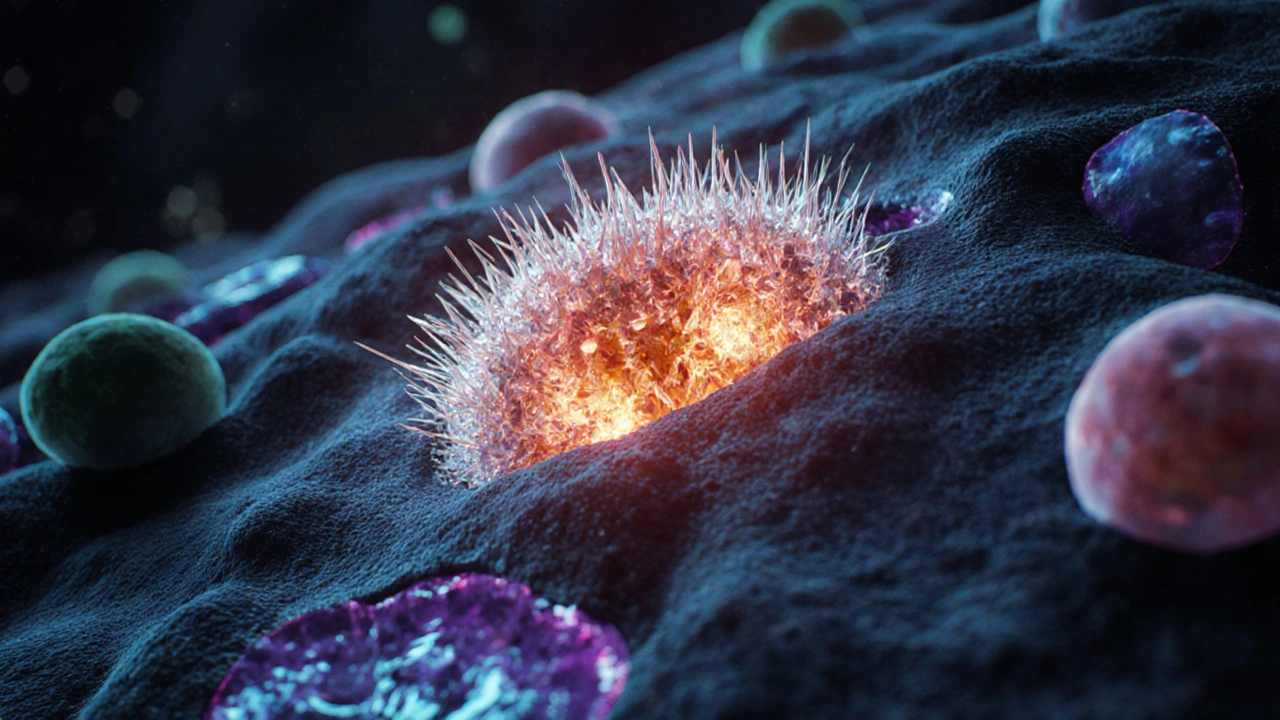

One of the most common companions of high uric acid is gout, a form of inflammatory arthritis caused by uric acid crystals depositing in joints. The relationship is simple: high uric acid encompasses gout, meaning the condition usually doesn’t appear without elevated levels first. Another frequent outcome is kidney stones, solid deposits that form when uric acid crystallizes in the urinary tract. Both gout and kidney stones share the same root cause—purine‑rich foods and reduced excretion. That’s why doctors often ask about diet, alcohol intake, and hydration when they see a spike in uric acid levels.

Key Factors That Influence Uric Acid Levels

Dietary purines are the primary fuel for uric acid production. Foods like red meat, organ meats, shellfish, and even certain legumes require the body to break down purine molecules, which then convert into uric acid. If you combine a high‑purine diet with limited water intake, the kidneys have a harder time flushing the excess out, leading to the buildup we call high uric acid. Genetics also plays a role; some people inherit a reduced ability to excrete uric acid, making them more prone to gout or stones even with moderate diets.

Weight, alcohol, and certain medications add extra layers to the puzzle. Obesity raises insulin resistance, which can slow uric acid clearance. Beer and spirits add both purines and alcohol, the latter of which dehydrates the body and spikes concentration. Diuretics, low‑dose aspirin, and some chemotherapy drugs hinder kidney function, pushing uric acid levels higher. Knowing these connections lets you target the right changes—whether it’s swapping steak for chicken, drinking more water, or discussing medication alternatives with a physician.

Monitoring is the first actionable step. A simple blood test reports uric acid levels, the concentration of uric acid in serum, usually measured in mg/dL. Values above 7 mg/dL for men and 6 mg/dL for women generally flag a problem. Once you have a baseline, you can track how lifestyle tweaks shift the number. Many online tools let you log foods and symptoms, turning raw data into a clear pattern of cause and effect.

Practical ways to bring the numbers down are surprisingly straightforward. First, hydrate—aim for at least 2‑3 liters of water a day. Second, moderate high‑purine foods; you don’t have to cut them out completely, just reduce portion size and frequency. Third, add alkaline foods like cherries, strawberries, and low‑fat dairy; research shows they can help the body excrete uric acid more efficiently. Finally, consider talking to a doctor about urate‑lowering medications such as allopurinol or febuxostat if lifestyle changes alone aren’t enough.

By keeping an eye on these factors, you transform high uric acid from a mystery lab result into a manageable part of your health routine. Below you’ll find a curated collection of articles that dive deeper into each aspect—dietary strategies, medication guides, symptom trackers, and more—so you can take confident steps toward lower uric acid and fewer painful flare‑ups.

How High Uric Acid Affects Your Immune System - Risks & Solutions

Explore how high uric acid levels activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, spark inflammation, and affect gout, kidney health, and immunity-plus diet and meds to restore balance.

© 2026. All rights reserved.